The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century split the Western Christian Church into territorial churches, even as it reaffirmed the role of the state to protect and promote Christianity. While the modern era brought with it political and then cultural secularization, the relationship between Christianity, political power, and cultural influence remains contested. This lecture will explore aspects of Reformation history relating to church and state and reflect on what Canadian Christians can learn for today.

To see the video version of this lecture (January 18, 2024), click here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K8LwaOyCU94&feature=youtu.be

Introduction

The premise of my talk is that we’re living in an age of tremendous social and political conflict often described as a “culture war,” and that Christians caught up in this conflict can learn much by looking back at an earlier culture war: the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century.

I think I first heard about culture wars sometime back in the 1990s, probably not long after sociologist James Davison Hunter wrote a book called Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America.[1] In it, he argued that a range of “hot button” issues like abortion, gun violence, homosexuality, and Christian politics were increasingly dividing the United States into two opposing camps that he called progressives and orthodox, the latter of which we might also call traditionalists.

In Canada and in many other countries, too, modernization, mobility, increasing social, ethnic, and religious diversity, rapid technological change, and growing cultural secularization have generated much conflict around a host of symbolic and identity issues. In every round of our culture wars, it seems, there are two irreconcilable positions. Polarization makes compromise difficult, even impossible, and this is because—beyond the specific issues—there is a larger debate here about the nature of moral truth. As Hunter explains it in his book, there are two opposing systems of moral understanding: progressives argue moral truth is contextual and can evolve; orthodox or traditionalists argue that moral truth is timeless, universal, and God-given.

We use the term “culture war” to describe this conflict, because both sides are trying to impose their beliefs, their values, their ideology on the rest of society. Culture wars are zero-sum games. For one side to win, the other must lose.

While Christians hold a wide range of views on so-called “hot button” issues, over the past decade a large block of conservative Christians in the United States and Canada has come to embrace a package of ideas that has been described as Christian nationalism or even white Christian nationalism. These Christians have garnered much media attention and political support for their reluctance to condemn colonialism and make restitution to Indigenous peoples, their unwillingness to accept the notion of systemic racism against people of colour, their strict adherence to traditional understandings of gender roles, gender identity, and sexual orientation, their resistance to public health measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic, their skepticism about climate change, and their overall rejection of political correctness and progressive identity politics.

Many Christian nationalists see current cultural trends as a disastrous rejection of Christianity. In the so-called Freedom Convoy of 2022, one protest banner bore the verse 2 Chronicles 7:14 “If My people who are called by My name will humble themselves, and pray and seek My face, and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven, and will forgive their sin and heal their land.” Another banner read “Jesus is the vaccine.” Thousands who donated to the convoy on the GiveSendGo crowdfunding site left comments about “God” and “Jesus,” suggesting they saw the Ottawa occupation in spiritual terms. Indeed, those occupying downtown Ottawa held impromptu church services and even contemplated a daily “Jericho march” around Parliament Hill.[2]

In the US, Christian nationalists have become even more extreme. As Christianity Today explained, Christian nationalism is the “belief that the American nation is defined by Christianity, and that the government should take active steps to keep it that way.”[3] What that means becomes clear in a recent Public Religion Research Institute survey, in which over half of US Republicans surveyed said that they “agree” or “completely agree” with the following five statements:

- The US government should declare America a Christian nation.

- US laws should be based on Christian values.

- If the US moves away from our Christian foundations, we will not have a country anymore.

- Being Christian is an important part of being truly American.

- God has called Christians to exercise dominion over all areas of American society.[4]

And so for many Christian nationalists, a setback in the culture wars feels like persecution, just as a victory looks like a sign of God’s favour. At the January 6, 2021, insurrection at the US Capitol in Washington D.C., one protestor clutched a “Holy Bible” in skeleton-gloved hands. Another held a large picture of Jesus wearing a red MAGA hat. Another held up a “Jesus saves” sign, while others carried flags that read “An Appeal to Heaven” and “Proud American Christian” as they stormed the Capitol.[5] Some American Christian nationalists would even abandon the long-standing US constitutional order and hand power to an authoritarian leader, if it would mean that their understanding of moral truth could be imposed on US society. The stakes are very high, indeed.

Back to the Reformation

But enough of our contemporary culture wars. What about that earlier culture war we call the Protestant Reformation? How well did Christians then manage to impose their understanding of moral truth—their beliefs, their values, and their ideology—on their society? The answer depends on where you look, but the story begins with the most famous sixteenth-century Reformer, Martin Luther.

Luther’s path to reform runs along two lines. Initially, his own spiritual anxiety led him to become a monk and then a scholar, eventually serving as Professor of Biblical Studies at the recently-founded University of Wittenberg, in Saxony, which was an important principality in the Holy Roman Empire. Luther’s study of Scripture—Psalms, Romans, Galatians, Hebrews—led him to understand that spiritual salvation was not something humans could contribute to, but had to come from the outside, as a merciful gift received by faith and grace. This discovery transformed Luther. “All at once,” he wrote, “I felt that I had been born again and entered into paradise itself through open gates.”[6]

But if Luther’s reform movement began with his own spiritual crisis, a second line ran from his studies and experience as a spiritual leader to his role as a bold critic of Catholic abuses, first and foremost around the Catholic practice of indulgences—that was the main point of his Ninety-Five Theses of October 1517—but then also of Catholic sacramental theology and papal authority. This too was rooted in Luther’s conviction about the authority of the Bible over Christian belief and practice.

And the criticisms were sharp. Luther and other reformers rejected the Roman Catholic doctrine of Purgatory as cynical and unbiblical, and condemned popular practices like indulgences and Masses for the dead, which were both purported to reduce the number of years the departed would be required to spend in Purgatory. Protestants argued these measures exploited the fear of death and undermined trust in the promise of salvation in Christ. Thus they coined the term “Totenfresserei,” or “feeding on the dead.”

There’s an arresting woodcut image, likely from the 1520s, which depicts a female devil who sits on a massive indulgence letter.[7] She (note!) holds an alms box in her right hand, eager to collect money, while her left foot rests in a chalice of holy water. Meanwhile, a demon carries a newly deceased pope through the air (the pope is holding the Key of St. Peter, in the centre of the left-hand side of the image) to a feast set on a table inside the devil’s mouth, where various monks await him. They feast on the bodies of ordinary Christian lay people, whose bodies are being dismembered, cured, and cooked by other demons, all over a raging fire on top of the devil’s head. So the clergy feast on the lay people, while the devil feasts on the clergy.

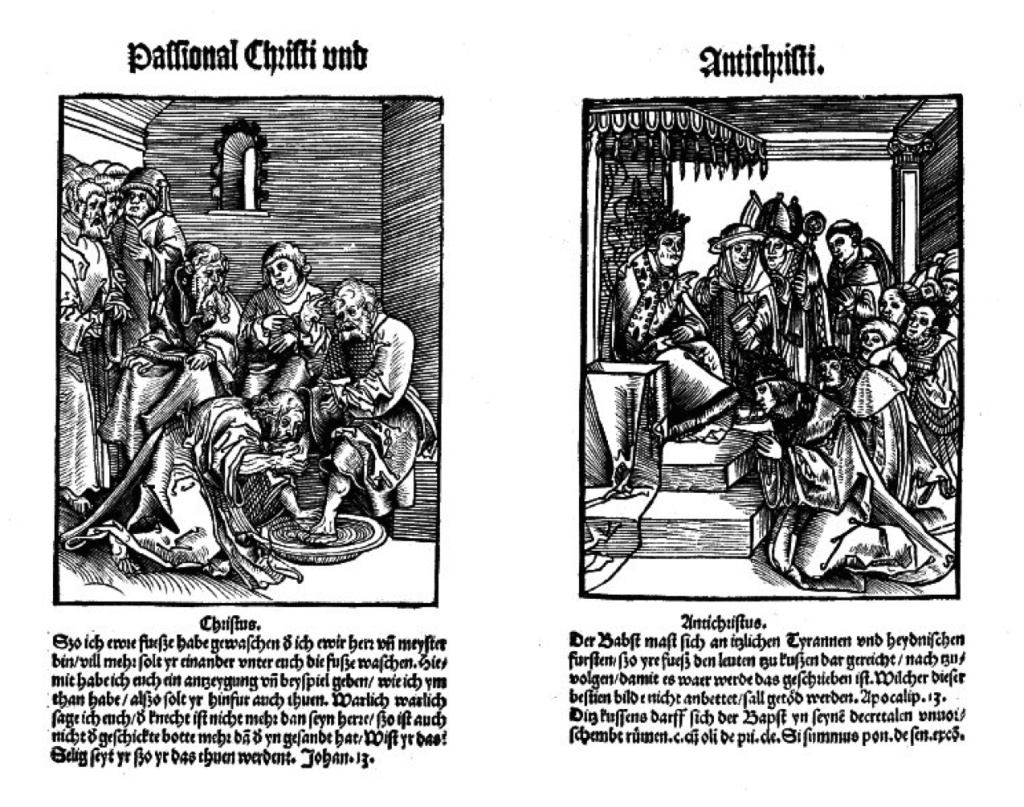

As Luther’s conflict with Rome deepened, his depiction of the papacy darkened. He came to regard the Roman Pope as the Antichrist, the Son of Satan. This idea was circulated widely in images associated with Luther’s reformation propaganda, such as in the 1521 Passion of Christ and Antichrist, by Lucas Cranach the Elder. In this work, the simplicity and humility of Jesus was repeatedly compared to the luxury and arrogance of the papacy. In one of twelve sets of contrasting images, Christ was depicted kissing the feet of the disciples as he washed them (John 13), while across the page the pope sat on his regal throne, accompanied by his clerical entourage, while groveling Christians lined up to kiss his feet.[8]

Another image by Lucas Cranach the Younger shows Luther’s preaching the message of Christ crucified for the sins of the world, while the pope and other Catholic clergy are driven by demons into the mouth of hell.[9] What the radical and violent nature of these depictions of the Catholics and Catholicism demonstrate was that, for Luther and his followers, the errors of the Roman Church and the papacy were not incidental, but fundamental and irreparable. They also show just how vitriolic the Protestant-Catholic culture war was. The stakes couldn’t have been higher—the eternal salvation of human souls hung in the balance.

The story of Luther’s Reformation was thus the story of a Christianity founded on the authority of Scripture over and against a Christianity founded on the institutional authority of the papacy. Time and again we see this, first in Luther’s 1518 Heidelberg disputation, at which he set forth his new theology in an assembly of his fellow Augustinian clergy; then again, in Luther’s encounter that same year with the papal envoy, Cardinal Cajetan, sent to Augsburg to hear Luther apologize and revoke his ideas—Luther refused, offering Cajetan a theological debate instead.

We see it again in Luther’s 1519 Leipzig Debate against Catholic theologian Johann Eck, at which Luther rejected the authority of both popes and church councils.

We see it in his reaction to the 1520 Papal Bull Exsurge Domine threatening him with excommunication, on account of his writings. Luther’s response was to burn the document and a copy of the Catholic canon law with it!

And we see it in the most famous moment of the Reformation: Luther’s 1521 trial at the Diet of Worms, the imperial assembly. Before Emperor Charles V, papal representatives, and the leading rulers of German states and cities, Luther refused to revoke his writings, arguing instead: “I stand convinced by the Scriptures to which I have appealed, and my conscience is taken captive by God’s word, I cannot and will not recant anything, for to act against our conscience is neither safe for us, nor open to us. Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me.”[10]

Here the reaction of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V is worth noting. Charles stood in a long line of Christian rulers who saw themselves as protectors of the Catholic Church. Indeed, the partnership between Catholicism and Holy Roman Emperors (as well as French, Spanish, and English kings and queens) was at the heart of the medieval idea of the res publica Christiana, the Christian Latin West. Within days, Charles issued the Edict of Worms, condemning Luther (who was already excommunicated by the Catholic Church) and placing him under the imperial ban—the political equivalent of excommunication.

The Edict of Worms also reflects the hostility and violence of the Reformation culture wars. Luther’s ideas are “heresies … drawn anew from hell.” If Luther isn’t stopped, “the whole German nation, and later all other nations, will be infected by this same disorder, and mighty dissolution and pitiable downfall of good morals, and of the peace and the Christian faith, will result.” Luther is “a madman plotting the manifest destruction of the holy Church.” His books and ideas arise out of “his depraved heart and mind.” He would “destroy obedience and authority of every kind.” Everything he writes “promote[s] sedition, discord, war, murder, robbery, and arson, and tend[s] toward the complete downfall of the Christian faith. For he teaches a loose, self-willed life, severed from all laws and wholly brutish; and he is a loose, self-willed man, who condemns and rejects all laws.”[11] I could go on, but you get the point. Charles V’s condemnation of Luther as a heretic paints the reformer as a danger to church, state, and society—one whose devilish ideas threaten both the eternal salvation of souls and the political survival of the empire.

So Luther was now a spiritual and political outlaw with a price on his head. His very survival depended on the protection of his ruler, Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony. Grateful though he was for Frederick’s favour, Luther still believed that only the power of the Word of God would carry the day. In a 1522 letter to Frederick, Luther explained that he was returning to Wittenberg (against the Elector’s wishes) but that it wasn’t up to the Saxon ruler to protect him: “The sword ought not and cannot help in a matter of this kind. God alone must do it—and without the solicitude and co-operation of men.” And as Lutheran church reforms were implemented in Wittenberg and surrounding communities, Luther insisted that his Reformation would not be implemented by force: “I will preach it, teach it, write it, but I will constrain no man by force, for faith must come freely without compulsion.” And as an example, he asserted that, I simply taught, preached, and wrote God’s Word; otherwise, I did nothing… [T]he Word so greatly weakened the papacy that no prince or emperor ever inflicted such losses upon it. I did nothing; the Word did everything.”

Over time, though, things changed. Luther soon discovered—much to his surprise—that although the Bible might be the authority for Christian belief and practice, others interpreted and applied the Scriptures differently than he did. For instance, German peasants wondered why—if all Christians were spiritually free in Christ and equal in the family of God—why they were held as the property of their aristocratic lords, forced to do labour without compensation and required to pay high rents and burdensome fees, all while they were oppressed by new laws and denied access to the common woods, streams, and fields on which they depended for food and fuel. Even as Luther denied his teachings justified these legal, political, and economic grievances, peasant uprisings exploded all over the Holy Roman Empire in 1525. Luther chastised the princes for the hardships of peasants, but ultimately sided with the rulers, urging “everyone who can [to] smite, slay, and stab, secretly or openly, remembering that nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful, or devilish than a rebel. It is just as when one must kill a mad dog; if you do not strike him, he will strike you, and a whole land with you.”[12] Estimates are that perhaps 100,000 peasants were slaughtered in the German Peasants’ War.

Now Luther’s Reformation came to depend more and more on the support of the state. In 1526, Elector John of Saxony (Frederick’s successor) sent out so-called “visitors” to inspect the churches. Soon, regular parish inspections were undertaken by state and church officials. In his 48-page instructions to these inspectors, Luther went on for no less than six pages about how the command to honour one’s father and mother extended to political authorities, who must be respected, honoured, loved, prayed for, and obeyed. Luther listed example after example from the Bible of how God punished those who rebelled against authority. “For we are to fear all temporal laws and ordinances as the will and law of God,” he wrote, even when these were burdensome or seemed unjust.[13]

But Luther still had to work out a theology that allowed for resistance over vital confessional issues. In 1531, after it was clear that the Holy Roman Empire had rejected the Lutheran Augsburg Confession—this is the point at which we can call Lutherans “Protestants” for their protest at the 1530 Diet of Augsburg—after it was clear that Emperor Charles V would not tolerate Lutheran Christianity, Luther wrote that “as theologians we are obliged to teach that a Christian is not to offer resistance [to temporal authorities] but to suffer everything.”[14] In the case of religious conflict, however, things were different. In his 1531 “Warning to his Dear German People,” Luther claimed he had always advocated for peace and that if a Catholic-Protestant war broke out, it wasn’t the fault of his teaching. Furthermore, “if the emperor should issue a call to arms against us on behalf of the pope or because of our teaching, as the papists at present horribly gloat and boast … no one should lend themselves to obey the emperor in this event. All may rest assured that God has strictly forbidden compliance with such a command of the emperor. Whoever does obey him can be certain that he is disobedient to God and will lose both body and soul eternally in the war.”[15]

Luther offered three justifications for this position. First, he argued that one’s baptismal vows required one to preserve the gospel of Christ. Second, the many abominations of the papacy justified resistance. Defending the Catholic Church was a participation in a “bottomless hell … with every sin.” Finally, resistance against the emperor would help preserve all the good that the Lutheran restoration of the gospel had produced. In closing, once more Luther denied he was spurring anyone to rebellion or even self-defence, and blamed “the papists” for any disruption of the peace. It was not, he declared, his doing.[16]

We do not have time to explore other reformers. Suffice it to say that John Calvin, the famous reformer of Geneva, adopted a similar position, absolutely condemning any resistance to state power. As he put it, “Although the Lord takes vengeance on unbridled domination, let us not therefore suppose that that vengeance is committed to us, to whom no command has been given but to obey and suffer.” But Calvin also opened the door for disobedience to rulers who “command anything against [God].”[17] Calvin’s examples (from Daniel, Jeroboam, and Hosea) make it clear that this resistance was meant for situations in which rulers commanded false worship—idolatry. In the violence of the French and Dutch Reformations, Calvin’s ideas grew into a full-fledged doctrine of resistance against unjust rulers when it came to defending the gospel—the Reformation teaching about salvation.

Again, we don’t have time to explore all the violent conflict that ensued, first in Germany, in the Schmalkaldic Wars, and then in the Swiss, French, Dutch, and English Wars of Religion, let alone the Thirty Years War that ended only in 1648 with the religious and political division of Europe. Thousands upon thousands of Europeans killed and were killed in conflicts that were fought by warring camps—both Christian, mind you—advocating opposing understandings of moral truth. Christianity and politics were tightly fused, and the result was an explosion of violence and destruction that lasted over a century. Here James Davison Hunter’s categories don’t quite work, because both Protestants and Catholics argued that they were the defenders of orthodoxy, of timeless, universal truth, just as both sides argued the other represented a progressive, novel, and dangerous version of “truth” That wasn’t truth. If you’ve never read accounts from these many wars of religion, I can tell you that the brutality of the conflicts is shocking. Fighting for versions of truth where the stakes seemed impossibly high—the eternal salvation of souls—meant that all manner of barbarism against human bodies was of minor importance. Tales of the burning of cities and towns and of wholesale slaughter appear regularly in the accounts of these culture wars.

Secularization

The irony of all this is that the sixteenth century culture war that was the Protestant Reformation played a key role in ushering in the secular politics of the modern era. German theologian Wolfhart Pannenberg captured this reality brilliantly in an article entitled, “How to Think About Secularism.” He argued that secularism wasn’t primarily apostacy from the Christian faith. Indeed, the strong emphasis on the human person that emerged during the Enlightenment and that was worked out in the American and French Revolutions has its foundations in Christianity. In fact, he suggests, we might say that modernity rescued Christianity from the intolerance of its sixteenth- and seventeenth-century culture wars. More importantly, he explains that the modern separation of church and state—the alienation of politics, economics, law, education, and the arts from the influence of the church—was (to quote him at length)

a result of the sixteenth-century Reformation or, more precisely, … a result of the religious wars that followed the breakup of the medieval Church. When in a number of countries no religious party could successfully impose its faith upon the entire society, the unity of the social order had to be based on a foundation other than religion. Moreover, religious conflict had proved to be destructive of the social order. In the second half of the seventeenth century, therefore, thoughtful people decided that, if social peace was to be restored, religion and the controversies associated with religion would have to be bracketed. In that decision was the birth of modern secular culture.

And Pannenberg continues his analysis—more from him:

After the wars of religion, the religious foundation of society, law, and culture was replaced by another, and that new foundation was called human nature. Thus there arose systems of natural law, natural morality, and even natural religion. And, of course, there was a natural theory of government, presented in the form of social contract theories. … Theories using human nature as the foundation of the political, legal, and cultural order made it possible for Europeans to put an end to the period of religious warfare. They also made possible, perhaps inevitable, the autonomy of a secular society and culture determinedly independent from the influence of church and religious tradition. [18]

Conclusion

So where does that leave us today? What can we learn from the Reformation culture wars that might help us navigate our own culture wars, in which Christianity once again plays an important role. I would suggest two key take-aways.

First, Reformation-era culture wars were not about peripheral issues. For Luther, Calvin, and other reformers and their followers, Reformation culture wars were high stakes affairs. At the heart of these conflicts were Christian understandings of salvation itself, and the eternal destiny of souls hung in the balance. This should make us cautious about which issues we believe justify resistance against political authority, or which issues we treat as worth the cost of open conflict in the public arena. Reformation theologies of resistance arose because fundamental understandings of salvation clashed, not because of concerns over particular rights or privileges of Christians. More specifically, although they were political, Reformation culture wars were about the salvation of people, not the Christianization of the state or society, something about which Jesus and New Testament authors have little to say.

The second takeaway is this: Reformation-era culture wars ultimately failed. They created immense division within society. They polarized families, churches, and communities. They led to incredible violence. And they brought Christianity into disrepute. They demonstrated only that the Christian faith was not a workable basis for society, government, law, or culture, because it was too intolerant, too inhospitable, too violent, too unloving. Simply put, religious culture wars led to the decline of Christian churches and the ousting of Christianity from politics, economics, law, public universities, and other institutions that underpin society.

In this sense, though the Protestant Reformation accomplished much good in reviving Christianity, it also serves as a cautionary tale about what happens when Christians attempt to force exclusive understandings of moral truth upon the wider society. Culture wars are zero sum games. For one to win, another must lose. The danger is that Christianity itself might be the loser.

[1] James Davison Hunter, Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America (New York: Basic Books, 1992).

[2] Christine Mitchell, “How white Christian nationalism is part of the ‘freedom convoy’ protests,” The Conversation, February 16, 2022, https://theconversation.com/how-white-christian-nationalism-is-part-of-the-freedom-convoy-protests-177113.

[3] Paul D. Miller, “What Is Christian Nationalism?” Christianity Today, February 3, 2021, https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2021/february-web-only/what-is-christian-nationalism.html.

[4] “A Christian Nation? Understanding the Threat of Christian Nationalism to American Democracy and Culture,” Public Religion Research Institute, February 8, 2023, https://www.prri.org/research/a-christian-nation-understanding-the-threat-of-christian-nationalism-to-american-democracy-and-culture/; Thomas B. Edsall, “‘The Embodiment of White Christian Nationalism in a Tailored Suit,’” New York Times, November 1, 2023, www.nytimes.com/2023/11/01/opinion/mike-johnson-christian-nationalim-speaker.html.

[5] Jack Jenkins, “How Christian nationalism paved the way for Jan. 6,” National Catholic Reporter, June 13, 2022, https://www.ncronline.org/news/politics/how-christian-nationalism-paved-way-jan-6.

[6] This is from Luther’s so-called “Tower Experience.” See Martin Luther, “Preface to the Latin Works” (1545), trans. Br. Andrew Thornton, OSB, from Luthers Werke in Auswahl, Vol. 4, ed. Otto Clemen, 6th ed. (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1967), 421-428.

[7] On Totenfresserei and the image of the she-devil feeding on the clergy, etc., see Steven Ozment, Protestants: The Birth of a Revolution (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 14-15.

[8] Lucas Cranach the Elder, “Passional Christi und Antichristi,” artbible.net, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32111661.

[9] Lucas Cranach the Younger, “Luther Preaching with the Pope in the Jaws of Hell,” Web Gallery of Art, https://www.wga.hu/html_m/c/cranach/lucas_y/y_luther.html.

[10] Martin Luther, “The Diet of Worms” (1521), in Documents of the Christian Church, ed. Henry Bettenson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1947), 282-285. I have substituted the more familiar “Here I stand” for Bettenson’s “On this I take my stand.”

[11]James Harvey Robinson, ed., trans., “The Edict of the Diet of Worms,” Readings in European History, Vol. 2 (Boston: Ginn and Company, 1906), 83-88.

[12] Martin Luther, Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants, in Carter Lindberg, ed., The European Reformations Sourcebook, 2nd ed. (Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, 2014), 98.

[13] Martin Luther, Instructions for the Visitors of Parish Pastors in Electoral Saxony, in Luther’s Works, 40, ed. Conrad Bergendoff (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1955), 286.

[14] Martin Luther, Letter to Lazarus Spengler in Nuremberg, in Lindberg, European Reformations Sourcebook, 149.

[15] Martin Luther, Dr. Martin Luther’s Warning to His Dear German People, in Lindberg, European Reformations Sourcebook, 149.

[16] Ibid., 149-150.

[17] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book 4, Chapter 20, Section 31 and 32, ed. and trans. by Henry Beveridge (Edinburg: Calvin Translation Society, 1845), http://www.ccel.org/ccel/calvin/institutes/.

[18] Wolfhart Pannenberg, “How to Think About Secularism,” First Things (June/July 1996): 28-29, https://www.firstthings.com/article/1996/06/how-to-think-about-secularism.